Americans are flocking to wildfire country

Over the last decade, there was an influx of Americans into regions where climate change is making wildfires and extreme heat more common, according to an analysis of multiple data sets done at the University of Vermont (UVM).

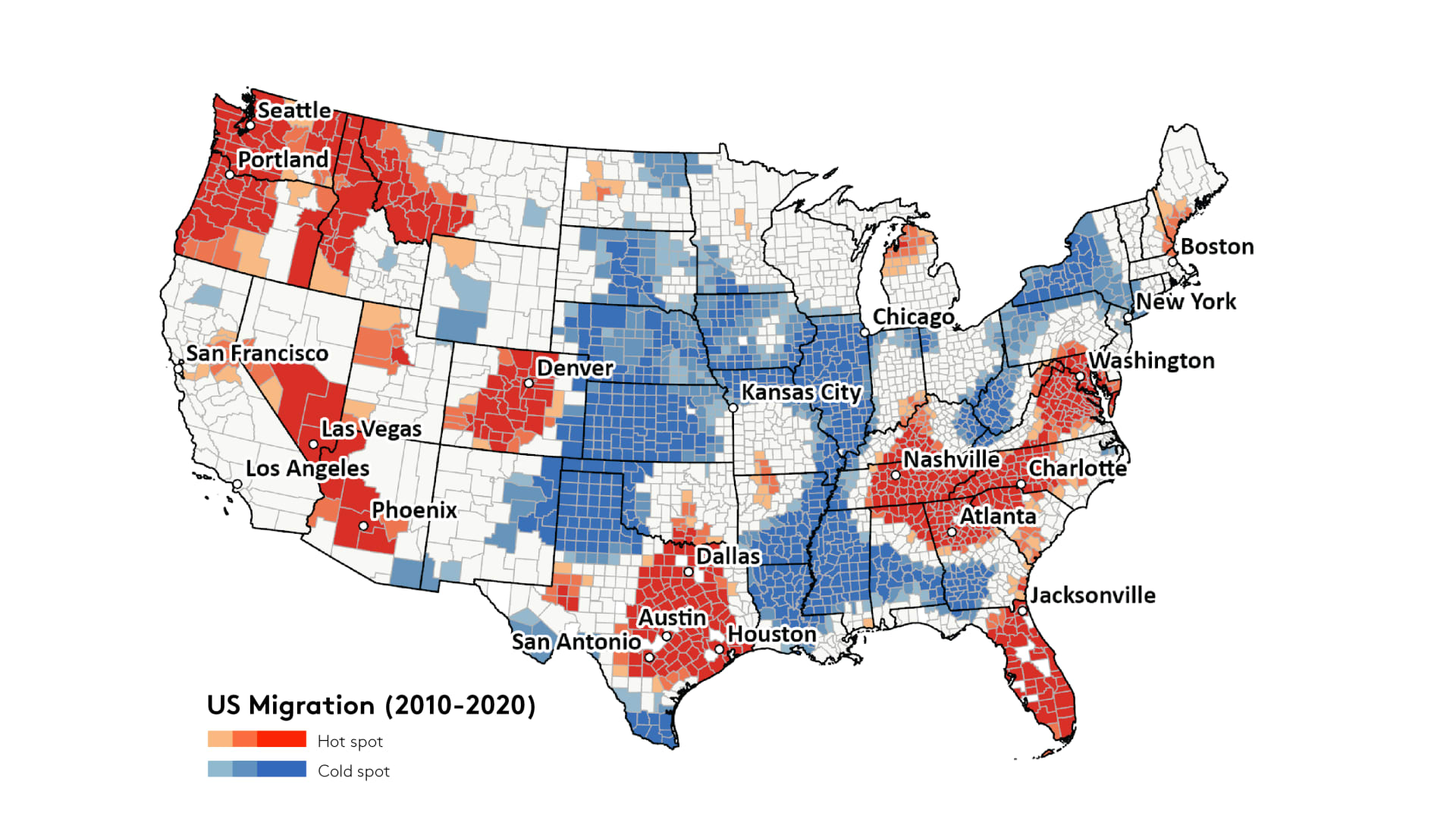

Broadly speaking, Americans migrated to the cities and suburbs in the Pacific Northwest, parts of the Southwest (in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Utah), Texas, Florida, and parts of the Southeast (including Nashville, Atlanta and Washington, D.C.), according to the research.

People moved away from the Midwest, the Great Plains, and from some of the counties that were hardest hit by hurricanes along the Mississippi River, according to the research.

“Our main finding is that people seem to be moving to counties with the highest wildfire risks, and cities and suburbs with relatively hot summers. This is concerning because wildfire and heat are only expected to become more dangerous with climate change,” Mahalia Clark, the lead author of the study, told CNBC.

Areas where more people moved into a region than out are red. Areas where more people moved out of a region than in are in blue.

Chart courtesy University of Vermont

“We hope our study will increase people’s awareness of wildfire and other climate risks when moving or buying a house, since many people might be unaware of these dangers,” Clark told CNBC. “People tend to think of wildfire as something that affects the West, but it also affects large areas of the South and even Midwest.”

For the research, Clark used multiple data sets, including net migration estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, the gridded surface Meteorological (gridMET) dataset hosted on the Google Earth Engine Data Catalog, and cloud cover data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The study was published on Thursday in the journal Frontiers in Human Dynamics.

Making decisions about where to live may be one of the first times that the ramifications of climate change impact people’s personal lives.

“People also tend to think of climate change as something that will affect our grandchildren, but its effects are already being seen in the form of more frequent and severe heat waves, hurricanes, and wildfires, and it’s important to take these effects into account when we plan for the future, both as individuals and as a society,” Clark told CNBC.

Deciding where to move and what home to buy is a complicated decision, and people have to weigh their own personal decisions based on job, family and culture, but Clark urges people to understand the trade-offs.

“It could be that wildfire-prone areas happen to be very attractive for other reasons (strong economy, pleasant climate, dramatic scenery with opportunities for outdoor recreation), and the perceived risks of wildfire are not sufficient to outweigh these other benefits,” Clark told CNBC. “People moving in from out of state may also be unaware of the risks. On the other hand, sometimes high risk areas are more affordable, creating an unfortunate incentive for people to move there.”

Wildfire probability, heat wave frequency and hurricane frequency across the United States.

Chart courtesy University of Vermont

Local authorities can play a part, too, Clark said.

“Development in wildfire prone areas can actually exacerbate risks, since increased human activity can spark more fires, so one implication of our work is that city planners may need to consider discouraging new development where fires are most likely or are difficult to fight,” Clark told CNBC. “At a minimum, policymakers should work to increase public awareness and preparedness and plan for sufficient fire prevention and response resources in high-risk areas with high population growth.”

The findings out of University of Vermont are “pretty consistent with what we’ve seen for the past 20 years with the two cycles of the census in terms of population growth in the Pacific Northwest” Jesse M. Keenan, a professor of sustainable real estate at Tulane University, told CNBC.

Climate change plays a role in the increased number of forest fires in the Pacific Northwest because the area is getting increasingly arid and dry.

“Basically, when it heats up in the atmosphere, you pull moisture, water out of the atmosphere, and that pulls it out of the biomass. So things basically just get dry, and therefore you have more fuel,” Keenan said.

Insurance companies are wising up to this and are pricing fire risk into the Pacific Northwest in ways that they hadn’t in the past, Keenan said.

But homebuyers also need to be doing their due diligence on the climate risks associated with the location where they are considering buying a new home. Keenan is an advisor to a company called ClimateCheck that helps identify these kinds of risks, but real estate websites now include “climate risk” factors like flood factor, storm risk, drought risk, heat risk and fire risk on listing pages.

These kinds of tools are helpful, but not perfect, Keenan said. Some of it comes down to common sense.

“If you live where there’s a fair amount of tree canopy near you, anywhere in the Pacific Northwest, you are at risk for forest fire,” Keenan said.